"I've been called the 'Maid mangaka,' the 'Liberty chaser,' and the 'lonesome hunter who can only draw maids.' I'm on the road today, too, on the lookout for maids!"

--

Kaoru Mori, in the author's notes for

Emma

Editor's Note: the images in this column are now clickable thumbnails. Click the art for the full-size version.

Maids, man. I just don't get it. I can see why people would like the combination of cute uniforms, loyalty and kinky subservience, but if that's what you want, what happened to good old robot girls, scantily clad ninjas and stranded space aliens? Maids have been popular in manga and anime for the last ten years or so, but it just isn't my thing, particularly when they're shoved into manga where they don't make any sense, like Hollywood studio executives converting movies into 3D for no real reason. If you're going to do a story about maids, better to set it in a time and place where people actually employ maids, like East Asian housemaids in the Middle East, Latino house help in Southern California, or maybe, like

Kaoru Mori's

Emma, maids in London in the 1890s.

Kaoru Mori really is a maid fan; before

Emma she wrote several other manga about maids, which are collected in her book

Shirley. Both manga were published in America by the now-defunct publisher CMX. (One of Mori's author notes contains the interesting detail that Western waitress uniforms were always modeled on maid uniforms, to give the customers "a taste of what it was like to be an aristocrat." So

all cafés are maid cafés deep down?) In Japan, her work is printed in the cult manga magazine

Comic Beam, which may have allowed her to develop her style in a more personal way, one that a high-circulation manga magazine wouldn't. Mori's maids aren't the dumb big-breasted maids you see in most shonen manga, or the frilly pretty I-wish-I-had-a-maid-uniform-too maids you occasionally see in

shojo. Mori is serious; she loves simple domestic scenes of housework and cooking and clothing, the kind that you see in a Miyazaki movie; she loves drawing cute girls and mature women and the interplay between servants and masters. And most of all, she loves the Victorian Era.

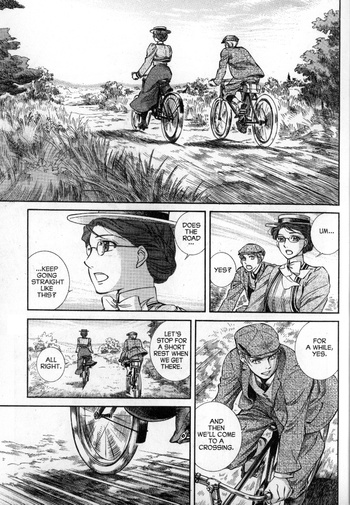

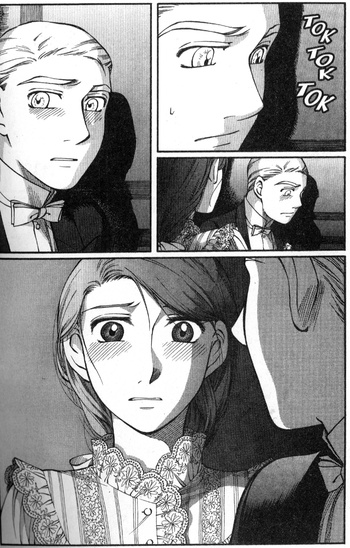

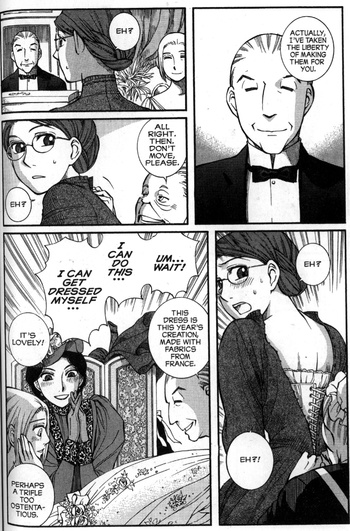

Emma is a romance, but it's also a loving recreation of Victorian England; not the grimy, dark England of Victorian hypocrisy, black lung and child labor, but the England of the Bronte sisters, of beautiful gardens and fancy balls, where women wear corsets and men wear top hats and everyone is so polite and proper they don't tell their true feelings.

Emma is a romantic fantasy set in a faraway land, the land of Victorian England, where the expectations of family and class clash against true love between a man and a maid.

That maid is Emma, a girl in her late teens with glasses who works as the only maid of an old lady, Ms. Stowner. Emma is kind and faithful and good at her work, but her quiet demeanor conceals her sad past; she was a poor girl from a remote village, and after her parents died she underwent a series of unfortunate events until she ended up as a beggar in London. She was saved when Kelly Stowner, a retired tutor, took her in and made her a maid. Kelly became Emma's surrogate mother, her teacher and her benefactor, teaching her to read and write and even to speak French (and presumably to lose her lower-class accent, since none of the characters in the manga ever talk about such a thing).

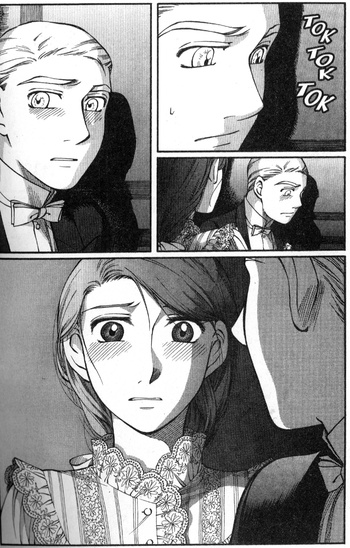

One day, one of Ms. Stowner's old students, William Jones, comes in for a visit. William, a businessman in his early twenties from a nouveau riche family, is just coming by to say his regards, but when he sees Emma, he's instantly smitten. They have a meet-cute when Emma bumps him in the face with the front door, and when their eyes meet, it just

happens: William is in love. He almost asks her out on a date right then and there, but instead he gets shy and leaves his glove in the house when he leaves so she'll have to go running after him to return it. He hangs out in the neighborhood hoping they'll run into one another, and he buys her a lace handkerchief. Emma soon recognizes William as the grown-up version of the little boy in the picture on her mistress's fireplace mantel, although she (like a proper ninja… I mean maid) tends not to display her emotions, she gradually warms to William as well. They go out on a date to

the Crystal Palace, one of the grand old public parks of London, and before too long, they share a kiss.

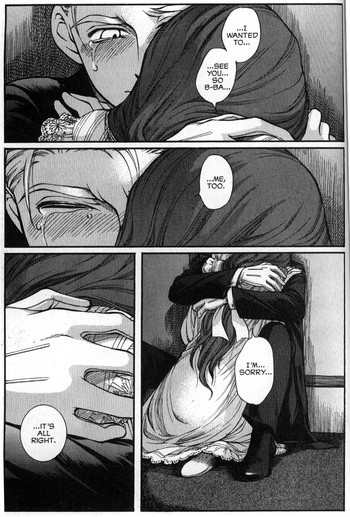

None of this escapes the eyes of wise old Ms. Stowner, but Ms. Stowner is a sympathetic sort. Although she realizes that a romance between a maid and a rich man will raise eyebrows in society, she likes William, and she realizes that she doesn't have long to live and she wants Emma to be happily married before she dies. But unfortunately for their love, William's family is not so understanding. William's father wants his son to marry a proper girl, such as cute Eleanor, a sweet girl who blushes when her shoulder accidentally touches William's while they sit together at a dinner party. The Jones are rich from their fabric business, but they are not of old upper-class stock, and William's father wants his son to "marry upward" so their descendants don't have to go through the same kind of prejudice that he himself went through when he was growing up. When William tells his father that he wants to marry a maid, his father threatens to disown him. Then Ms. Stowner dies, and a grieving Emma decides that her presence will only hurt William and that the two of them can never be married. Leaving William a farewell note, she leaves London without telling him where she's going, setting out on her own to work as a maid for a new family, to try to start over, to forget.

This is the basic plot of the first three volumes of

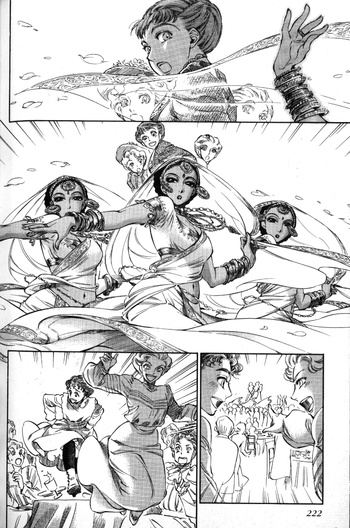

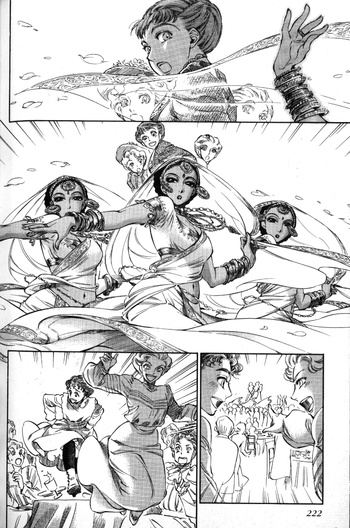

Emma, a seven-volume series (volumes 8-10 consist mostly of side stories about the supporting cast). But of course, there's much, much more. Mori introduces us to a huge cast of quirky characters out of a dream of the Victorian Era. There's Monica, Eleanor's overprotective big sister, a commanding young woman who rides around on horseback like a man and defends her little sister's honor with an almost

Lady Oscar-esque machismo. There's William's friend Hakim, the stereotypical Indian prince who never travels without his parade of elephants and his harem of

sari-clad dancing girls, stretching the realism of the series to the point of breaking (they

are nicely drawn elephants, though). Since Hakim doesn't understand social graces the way the other characters do ('cause he's a foreigner! Oh the hilarity!), he pushes the plot along and pushes Emma and William to get together. There's Viscount Campbell, the one truly evil character of the series, who consents to shake the hand of a "commoner" but then throws his gloves away later, when the man isn't looking. There's a ton of cute girls and little old ladies, and there are moments that feel like they could have come from a Victorian romantic comedy, such as the scene when Eliza, a noble girl, is telling her friends what kind of man she wants: income over 80,000 pounds, a four-horse carriage, tons of servants, good family, brown hair and grey eyes, etc. When they suggest someone who meets her criteria, she haughtily answers "Never! It'd seem like I was marrying him for his money! I'm hoping to marry my true love!"

And it's in true love, in the troubled hearts of Emma and William, where

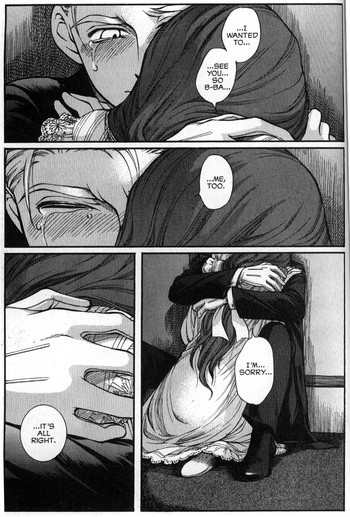

Emma succeeds as a story… and also where it stumbles a little. As I tried to indicate in my description, the hero and heroine fall in love a little quickly. They could have used a little more dialogue together; conversation between the lovers is kinda important in a romance, but the relationship between Emma and William develops so fast that we don't really see much except their eyes meeting a few times, and then presto. Mori also has a habit of putting the volume on mute during important dialogue, so that we must figure out what's being said from the characters' expressions. It's not a bad thing, but sometimes I'd like more dialogue. William's shy crush is cute to watch, but Mori doesn't do the best job of conveying why William falls for her: of course love at first sight can be beyond logical explanation, but is it her gracefulness? Her face, which looks a bit schoolmarmish with those glasses and that bun? It's certainly not their conversational skills. It's not just William who loves her, either; Hakim, too, falls instantly in love with Emma and tells her so on their first meeting. Apparently noblemen are continually falling in love with shopgirls and maids in Mori's universe.

Emma doesn't realistically depict the class prejudice (or race prejudice, speaking of Hakim) that existed in the Victorian era; in real Victorian days, a romance between a maid and an upperclassman would be more likely to end with an affair and an unplanned pregnancy, but never mind that;

Emma is a more innocent manga.

But if the romance between Emma and William is a little clunky at the beginning, it really blossoms after they're forced to part ways. Once Emma and William are parted, Mori does a good job of showing their longing and loneliness, with the odd effect that their love for one another seems more real when they're alone; maybe absence really does make the heart grow fonder. Emma finds a new job and a new household, a boisterous house where the cheerful, gossipy servants have big parties in the kitchen after the family of the house has gone to bed. William tries to lose himself in his work, and since Goths didn't exist yet in the Victorian Era, he reads sad romances and the depressing philosophy of

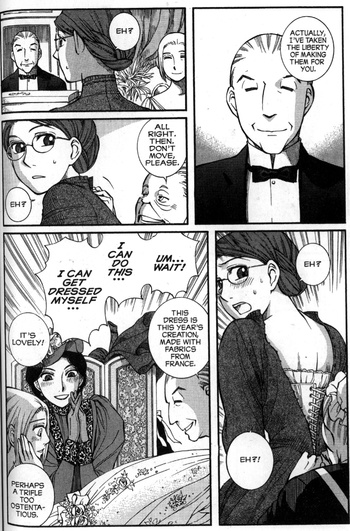

Arthur Schopenhauer. And, most interestingly, Emma starts to grow up and become more of a human being. For most of the manga, Emma is such a perfect, devoted maid that she's sort of a blank slate; she doesn't even have a last name. Her life starts to change when she meets two exceptional women. One is the mistress of her new house, Mrs. Meredith, a beautiful, sexy married woman who is so at ease with her own body and has such an equal relationship with her husband that Emma, for the first time, starts to conquer her shyness about her body and sees an example of what a successful marriage could be like. Another is Mrs. Trollop (actually that's just her pseudonym, but to say more would be a spoiler), an eccentric middle-aged woman who keeps a pet monkey and decorates her mansion with ferns and elaborate Japanese prints. Mrs. Trollop takes a fancy for Emma and even dresses her up and takes her to a ball. In part, Mrs. Meredith and Mrs. Trollop are the standard 'rich benefactor' characters who appear throughout Victorian fiction as a

deus ex machina for hard-working young do-gooders, but they also inspire Emma to come out of her shell and show her human side. It's not much of a spoiler to say that Emma and William eventually meet again, but there are tears and obstacles before they can be together. It's the chaste, bittersweet longing between two souls forced to hide how they really feel that makes

Emma feel like a true Victorian romance.

But despite all the characters (of which there are many) and plot twists (of which there are actually not so many), in the end,

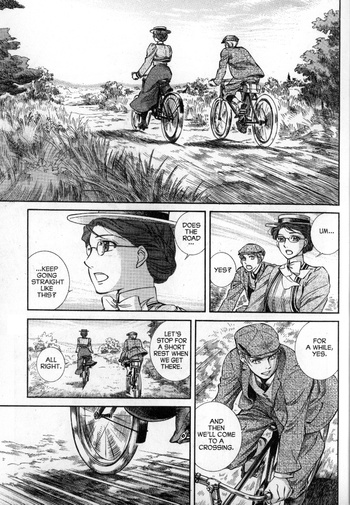

Emma is mostly a manga about setting. Many of

Kaoru Mori's characters look similar to one another, and she's not a great artist for faces and facial expressions, although she makes up for this with her pacing and storytelling. On the other hand, she is very good at drawing realistically proportioned human bodies, which you can see in the manga's occasional nude scenes, which all involves bathing or people putting on clothes. (There are long, lingering scenes of Emma putting on her maid uniform, but oddly, it's mostly other characters, not Emma, who appear naked.) But mostly, she is amazing at backgrounds. Her crosshatching just gets more and more meticulous (compare it to her early work in

Shirley if you want to see how much an artist can improve in a few years) and her backgrounds get better and better. Mori obviously takes pride in her historical research (although there's still a few anachronisms, like the pre-1903 model plane which was changed to a model train in the anime), and she doesn't just tell us about it, she

shows us, showing us Victorian clothing, wash tubs, furniture, and cooking equipment. When Emma cleans the house, it's like she's making the world sparkle to better show off Mori's creations. Of course, making things sparkle is hard work; there's a nice scene at a dinner party, where the upper-class dinner guests elegantly dine on refined foods, while behind the kitchen doors, the cooks run around in the steam and smoke yelling and hustling make sure everything looks perfect for the noblemen. Some of the best scenes in

Emma are silent, beautiful scenes when we can almost imagine that we are there in the picture: a boat ride on a lake, where a girl brushes her hand through the water; the wind in the trees and along the grass as Emma stands alone; lovely Victorian drawing-rooms with the shadows making patterns on the wainscoting. In one of the early flashback scenes, Emma gets her first pair of glasses and is amazed by how beautiful the world looks. The real achievement of

Emma is not just making us love the characters, but making us love their world and want to be in it.

Emma is not a perfect manga. It feels a bit padded out; there are a lot of scenes where nothing happens, scenes of Victorian life "just because," and lots of unimportant dialogue of the "Can I have some tea?" "Sure!" "Thanks for the tea! "My pleasure!" type. The brief detour into

Perils of Pauline melodrama towards the end doesn't work very well or seem very well thought-out;

Emma is too darn

nice a manga to convincingly introduce an element of physical peril. It doesn't even have much emotional violence; it'

S.A manga about touches and glances and regrets and social obligations, and finding the courage to chase after the one you love. But Mori is an interesting creator with a unique style, and I'm looking forward to her latest work,

A Bride's Story, about a teenage girl from a nomadic culture in the Central Asian steppes, sometime in the 19th century, who is engaged to an eleven-year-old boy.

A Bride's Story has all of Mori's love of history and exotic settings, combined with a very badass heroine who can ride a horse and hunt and generally take good care of her child-husband. The first volume is being published by

Yen Press in May, a good as well as arguably brave publishing decision, since at least one other manga publisher I know rejected it because of the age difference between the love interests (even though they don't really…you don't see them…you know…).

Kaoru Mori is a better artist than a writer, but I'd gladly lose myself in the rich worlds she creates.

In an article devoted to the ongoing

In an article devoted to the ongoing  In an interview in the May issue of Enterbrain's Otona Fami magazine on Friday, director

In an interview in the May issue of Enterbrain's Otona Fami magazine on Friday, director  The retails news source ICv2

The retails news source ICv2

Новый выпуск журнала Dragon Magazine издательства Fujimi Shobo сообщил, что ранобэ Seitokai no Ichizon автора Секина Аой получит еще одну аниме адаптацию. Ранобэ Seitokai no Ichizon уже вдохновил на одноименный аниме сериал в 2009 году.

Новый выпуск журнала Dragon Magazine издательства Fujimi Shobo сообщил, что ранобэ Seitokai no Ichizon автора Секина Аой получит еще одну аниме адаптацию. Ранобэ Seitokai no Ichizon уже вдохновил на одноименный аниме сериал в 2009 году.